Daylight Savings Time (DST) is the practice of moving clocks forward by one hour during the warmer months of the year, typically in spring, to make better use of natural daylight in the evenings. In the fall, clocks are moved back one hour to return to “standard time.”

The purpose of DST is to conserve energy by reducing the need for artificial lighting in the evening and to provide more usable daylight hours after work or school.

While it was originally tied to energy savings, modern studies show the actual savings are small or negligible. Critics also point out negative effects such as sleep disruption and potential health issues.

The History of Daylight Savings Time

Early Concepts

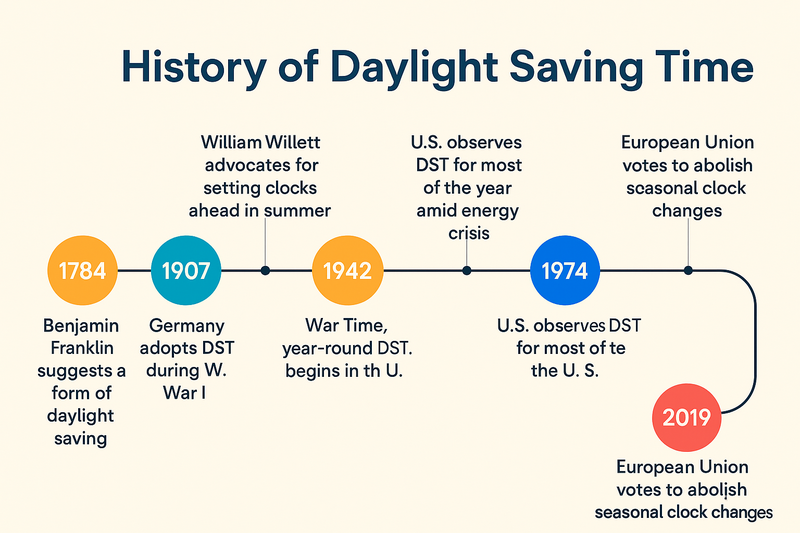

1784 – Benjamin Franklin

- Franklin wrote a satirical essay suggesting that Parisians could save candles by getting up earlier and making better use of daylight. This was not a proposal for changing clocks, but it introduced the idea of aligning schedules with daylight.

1895 – George Vernon Hudson (New Zealand)

- Hudson, an entomologist, formally proposed a 2-hour daylight saving shift to allow more daylight for his insect-collecting hobby. His idea gained some attention but wasn’t adopted then.

1907 – William Willett (England)

- Willett campaigned in Britain for advancing clocks in the summer to save energy and encourage outdoor activities. His proposal influenced later adoption, though he died before seeing it implemented.

Wartime Adoption

World War I (1916)

- Germany and Austria-Hungary were the first nations to adopt DST on April 30, 1916, as a way to conserve coal during wartime.

- Britain, France, and many other European nations soon followed.

- The United States implemented DST in 1918, but it was unpopular and repealed after the war.

World War II (1940s)

- DST returned as an energy-saving measure. In the U.S., it was called “War Time” and lasted from 1942 to 1945. After the war, states and localities decided individually whether to use DST, creating widespread inconsistency.

Post-War Confusion and Standardization

1945–1966 (U.S.)

- Different cities and states followed different rules. For example, traveling by train across states meant adjusting to multiple time changes within a single day.

1966 – Uniform Time Act (U.S.)

- Congress passed this law to bring order, requiring states to follow a standardized DST schedule if they chose to observe it. States were allowed to opt out entirely but not to create their own rules.

Energy Crises and Adjustments

1970s Oil Crisis

- In response to energy shortages, the U.S. extended DST to conserve electricity.

1986 & 2005 Adjustments (U.S.)

- In 1986, DST in the U.S. was lengthened to start earlier in spring.

- In 2005, the Energy Policy Act extended DST further, beginning in 2007 with the current U.S. schedule (second Sunday in March to first Sunday in November).

Global Use

– DST spread to many countries in Europe, North America, and parts of the Middle East.

– Many countries in Africa, Asia, and South America have tried it but discontinued due to minimal benefits near the equator (where daylight hours don’t vary much).

– In recent decades, several countries (e.g., Russia, Turkey, Argentina) have abandoned DST, citing health concerns and limited energy savings.

Present Day

- United States: Still observes DST (except most of Arizona, Hawaii, and U.S. territories).

- European Union: Voted in 2019 to abolish seasonal clock changes, but implementation has been delayed.

- Worldwide Trend: Fewer countries use DST today compared to the mid-20th century.

Daylight Savings Time began as a wartime energy-saving measure in 1916, was standardized in the U.S. in 1966, and has been extended several times since. While it aimed to save energy and give people more daylight in the evenings, today its benefits are debated, and many regions have abandoned it.

Fun Fact: The correct way to say Daylight Savings Time is actually the singular version without the “s”: Daylight Saving Time. People got so used to saying it with the “s” that its become the norm.